The Who’s Tommy is on stage starting June 13!

GET TICKETS

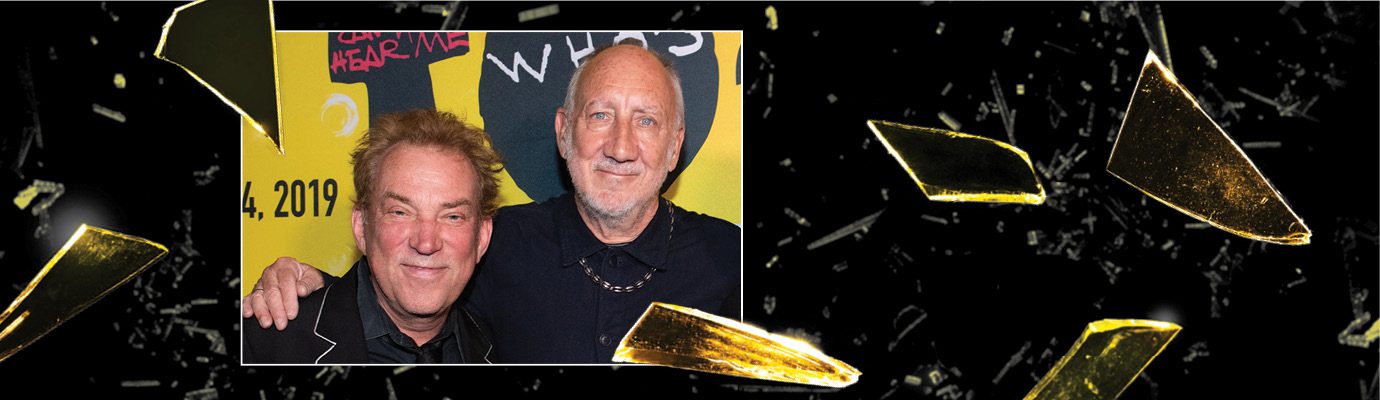

Director Des McAnuff, who co-wrote the stage version of The Who’s Tommy with rock legend, Pete Townshend, reimagines the show for listeners old and new

By Thomas Connors

Woodstock was still two months away and the trial of the Chicago Seven had yet to begin when British band, The Who, released Tommy in May 1969. Composed by guitarist Pete Townshend as a rock opera, the ambitiously-conceived double album told the tale of a boy so traumatized by seeing his father shoot his mother’s lover that he goes mute and loses his senses of sight and hearing. Tommy Walker remains isolated within the multi-layered dysfunction of his family until he demonstrates a powerful ability to play pinball—and the world rushes in. In 1993, two-time Tony Award-winning director, Des McAnuff, teamed up with Townshend to bring the story to the stage. As he preps for a 30th anniversary production at the Goodman, McAnuff shares his thoughts on Tommy then and now.

THOMAS CONNORS: How did you become attached to this project 30 years ago?

DES MCANUFF: My partner at Dodger productions, Michael David, put me and Pete Townshend together. He thought that I might be a good collaborator. We got along incredibly well, right from the get-go. We first met in the lobby of the Portobello Hotel in London, just the two of us, for several hours. Then we started in earnest, meeting in New York, spending hours over several months cooking this thing up. Pete warned me that he might not be able to get too involved, but as it turned out, he gave all kinds of effort and inspiration to this and the project benefited tremendously from that.

TC: There’s at least one generation now who may not know the original album, or your initial production at La Jolla Playhouse. Can you say something about your commitment to the material and your conviction that it has staying power?

DM: I think Tommy is the greatest of what we used to call ‘concept’ albums. It is just an extraordinary score, with Pete as the principal creator. There are young people who aren’t going to be aware of Tommy, for sure, but it’s astonishing to me how many young people really have a broad appetite for all kinds of music. I was at a concert with my daughter to hear The National and before they came on, music was being piped in and she said, ‘Oh listen, it’s Iggy.’ It was Iggy and The Stooges. I said, “How can you possibly know that?” And it was because she has an interest in all genres.

TC: When the album came out, Nixon was in the White House, we were still in Vietnam—the country was facing all kinds of political and generational conflict. How do you suppose Townshend’s narrative registers today?

DM: I think, in many ways, the world has caught up with Tommy Walker. Today, the whole world seems to be looking into a mirror—as Tommy does—albeit a very black mirror. Tommy Walker, an anti-hero, rejected human existence as we know it. And I think, with the trauma people have experienced lately, that that makes a lot of sense right now. Many people want to escape from a world they consider hostile or threatening. Another aspect of the show that I find pertinent is the willingness of people to follow a guru, or leader, even if that means going over the edge of a cliff. That’s Tommy’s major epiphany in the second half of the story, when he realizes how dangerous it is that people are turning to him and expecting him to answer questions that he can’t.

TC: Tommy faces a lot of bullying and even abuse, which people can feel very sensitive about seeing depicted onstage. Have you felt the need to mediate that in any way with this latest production of the show?

DM: Our attitudes constantly evolve, but it’s important to take things in context. I think of Hal’s description of Falstaff, “that trunk of humours, that bolting-hutch of beastliness, that swollen parcel of dropsies.” That would be considered the worst kind of fat shaming now. Yet considering the timeline on which that play exists, I wouldn’t feel compelled to re-write that speech and make it palatable by today’s standards. Tommy is abused, but the story isn’t celebrating that abuse, it’s condemning it. I think we have to take on difficult subjects. I am not compelled to clean Tommy up. On the other hand, I want the production to have a very clear point of view.

Thomas Connors is a Chicago-based freelance writer and the Chicago Editor of Playbill.